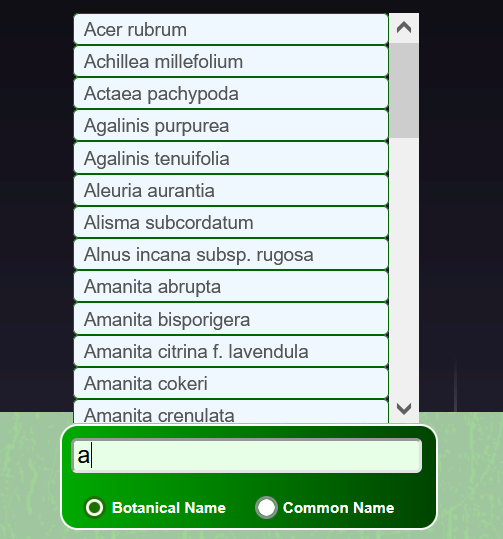

Navigation: The Header Navigation bar contains six

clickable Icons. They are:1)Plant Type, 2)Sun Exposure, 3)Moisture Level,

4)Plant Height, 5)Bloom Season, and

6)Flower Color.

contains six

clickable Icons. They are:1)Plant Type, 2)Sun Exposure, 3)Moisture Level,

4)Plant Height, 5)Bloom Season, and

6)Flower Color.

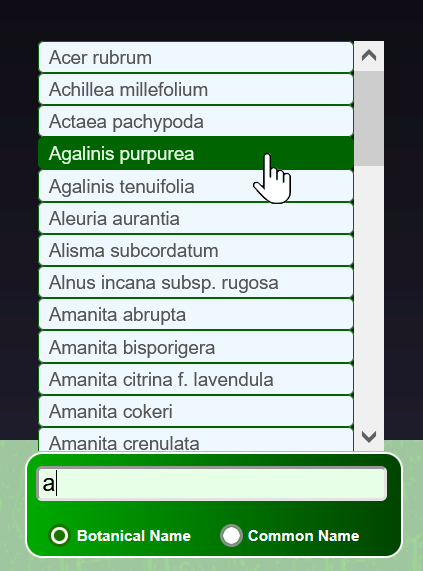

When one of the icons in the header navigation bar is clicked/selected, such as 'Plant Type ', a list of choices will appear on the left side of the screen as a Side Navigation Menu

', a list of choices will appear on the left side of the screen as a Side Navigation Menu . There will be between four to nine

items to chose from, depending on which of the icons has been selected.

. There will be between four to nine

items to chose from, depending on which of the icons has been selected.

When one of the side navigation menu items is chosen/clicked, in this case 'Perennials', a Group of Photos appearing

in alphabetical order by botanical name will be displayed in the center of the page.

appearing

in alphabetical order by botanical name will be displayed in the center of the page.

Within the silver bar, located above every individual plant photo, is the plant's ' Botanical Name ', aka the latin

name, the one that everyone hates, but is crutial for conveying proper identification. Over time, plants have accumulated many different common names; depending on what part of the world, country, or state that you live in, a

plant could potentially have a different common name in many different locations across the globe. This confusion, created by the use of different names, has often lead to inaccurate plant identifications.

', aka the latin

name, the one that everyone hates, but is crutial for conveying proper identification. Over time, plants have accumulated many different common names; depending on what part of the world, country, or state that you live in, a

plant could potentially have a different common name in many different locations across the globe. This confusion, created by the use of different names, has often lead to inaccurate plant identifications.

A plant's official name conforms to the International Code of Nomenclature whose current version, the Shenzhen Code, was adopted by the International Botanical Congress held in Shenzhen, China, in July 2017, and

its final form was published on June 26, 2018. The use of formal names is meant to prevent potential misunderstandings and misidentification of a plant species.

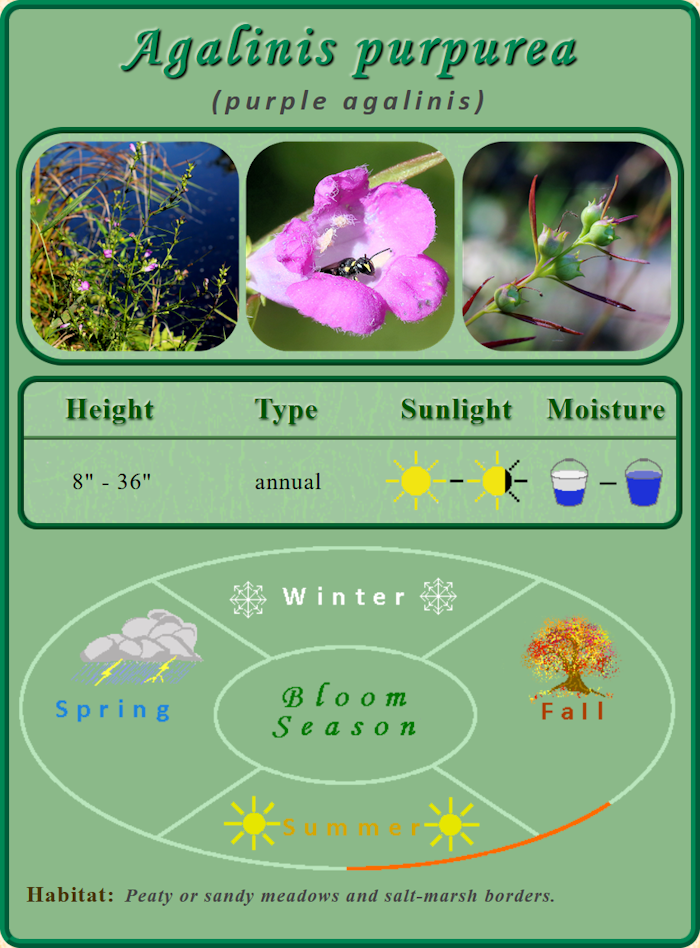

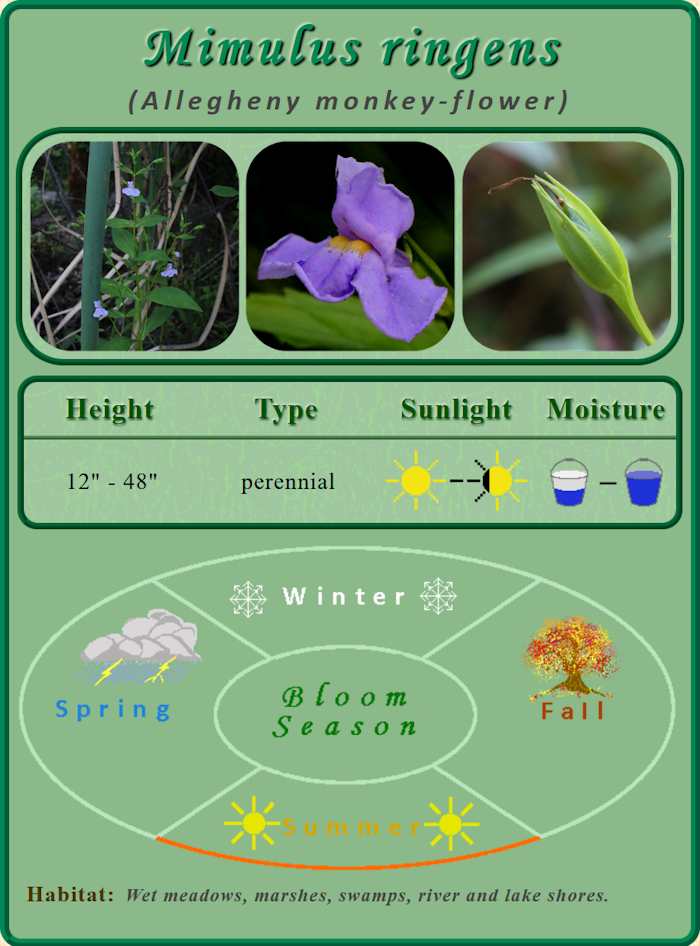

The silver bar, in which the botanical name resides, is actually a hyperlink

that brings you to a more Detailed Description of the selected plant; in this case, Achillea millefolium has been selected.

of the selected plant; in this case, Achillea millefolium has been selected.

- Plant Type (7 choices): They are:

1)Perennials, 2)Annuals and Biennials, 3)Grasses-Rushes-Sedges,

4)Trees and Shrubs, 5)Ferns, 6)Mushrooms and Fungi,

and 7)Lichens and

Mosses.

I took a few liberties with this group, as I often come across mushrooms, polypores, slime molds, and lichens, all of which are not plants...So, what was I to do; I could not just pass these extraordinary life forms by! Somehow, I think it was by magic, they managed to sneak their way into this category.😇

These wonders of nature, as primitive, complex and fascinating as they are, have their very own special appeal; they just beg to be noticed, and deservedly so! More on them later, but for right now, here are the Plants... - Perennials: This group is dedicated to the herbaceous perennials, those plants that die

back to the ground each year and re-emerge in the spring; they survive the winter and adverse conditions by storing food/energy in their specialized root systems. Below are four plants, each of which use a different type

of specialized root:

First is the woodland perennial, Claytonia caroliniana (Carolina Spring-Beauty), which emerges from a special root known as a cormA vertical, solid-tissued, fleshy, underground stem that acts as a food-storage structure in certain seed plants. It bears scaly leaves and buds, and many produce offshoots known as cormels that are used for vegetative reproduction.

Next, is the sun-loving Lilium philadelphicum (wood lily), which is a plant that grows from a bulbA layered, modified stem that is the resting stage of certain seed plants. A bulb consists of a relatively large, usually globe-shaped, underground bud with fleshy overlapping leaves arising from a short stem; many of them produce offshoots known as bulblets that are used for vegetative reproduction.

The moisture-loving perennial, Caltha palustris (marsh marigold), is an example of a plant that sprouts up from special roots known as rhizomesA rhizome is a horizontal underground plant stem capable of producing the shoot and root systems of a new plant. In addition, those modified stems allow the parent plant to propagate vegetatively.

and lastly, if you are fortunate enough to come across Rhexia virginica (Virginia meadow beauty), you have found a plant that develops from a tuber A fleshy, usually oblong or rounded thickening or outgrowth of an underground stem or shoot, bearing minute scalelike leaves with buds or eyes in their axils from which new plants may arise..

- Annuals and Biennials: These are a group of plants that either complete their life cycle

in one year or grow leaves, usually in the form of a rossette the first year, then flower the second year. I was quite surprised as to just how many of our native plants fit into this category.

- Grasses, Rushes, and Sedges: I was not expecting to find many plants to enter into this

group but was pleasantly surprised. I was also pleasantly surprised, because I never gave them much thought, that these plants encompassed such a wide variety of sizes and shapes.

- Trees and Shrubs: This group, as one would expect, has a great deal of variation in height.

This group includes the dainty, trailing, subshrub, Mitchella repens (partridgeberry), which is no more than a few inches tall and this beauty; the massive, picturesque tree, Platanus occidentalis (American sycamore),

which can reach a height of 100'.

- Ferns: I have always photographed ferns from above, not knowing that the key to

identifying many of our native ferns is the size, shape, and placement of the sori One of the clusters of sporangia on the back of the fronds of ferns. (sporangium: the case or sac in

which spores are produced.) (sorus: plural of sori) on the underside of the frond The leaf or leaflike part of a palm, fern, or similar plant. These are called fronds to

distinguish them from the leaves of flowering plants. Leaves in flowering plants are purely concerned with photosynthesis whereas fern fronds have both a photosynthetic function and a reproductive function..

Dryopteris marginalis (marginal wood fern) was given both its species name and common name due to the placement of the sori along the margin of its pinnulesA secondary division of a pinnate(compound) leaf, especially of a fern; a pinnule can be further divided into what is called a pinnulet.. There are, of course, some ferns that are easy to recognize by sight alone. One such fern is the unique-looking, Osmunda regalis (royal fern), whose leaves look more lupine-like than fern-like.

- Mushrooms, Fungi, and Slime Molds: These are non-plants; they are primitive

life forms, ones that I've come to appreciate, and also, ones that I know very little about. Most of the literature that I read pressed the point that many mushrooms can only be positively identified by the size, shape,

and color of the spores, as well as a chemical reaction which occurs when exposed to certain substances. I had to do a lot of research for these and some ID's are probably incorrect; any help is

greatly appreciated. Thank you!

Having said that, I did my best with these by looking at other parts of the mushroom: gills, cap, stalk, bruising, and others, all of which may help with an identification. One great site that I found for beginners like me is 'Mushroom Appreciation', which has some great tips for mushroom identification.

For those of you who are a bit more advanced, Micheal Kuo's site, 'The Mushroom Expert.com', is the site for you; he is quite knowledgeable, and quite funny.

There is also a book available for identifying mushrooms in our area; it is titled: Mushrooms of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada (A Timber Press Field Guide) Flexibound ? Illustrated, July 12, 2017

One thing is for certain about this category: it has an array of different sizes, shapes and colors.

- Lichens, Mosses, and Liverworts: This is a 'simple plant' and 'non-plant' category. On one

hand, mosses and liverworts are tiny simple plants that produce spores instead of flowers and seeds.

On the other hand, a lichen is not a plant at all; it is, instead, a stable symbioticBiology: A close and prolonged interaction between organisms of different species.

There are three types of symbiosis: mutualism, (beneficial for both), commensalism (beneficial for one, neutral for the other), and parasitism (beneficial for one, costly for the other). association between a

fungus, algae, and perhaps what is known as cyanobacteriaCyanobacteria, formerly known as blue-green algae, are photosynthetic microscopic organisms that are technically bacteria. They

are found in all lakes and are a natural part of the lake ecosystem. In addition to being photosynthetic, many species of cyanobacteria can also "fix" atmospheric nitrogen-that is, they can transform the gaseous nitrogen

of the air into compounds that can be used by living cells. Various types of associations take place between cyanobacteria and other organisms. Certain species, for example, grow in a mutualistic relationship with fungi,

forming composite organisms known as lichens.. As with the mushrooms, this is also a group that I know very little about, so some of my ID's may be incorrect; once again, any help is

greatly appreciated, and Thank you!

I have always been intrigued by these life forms; although quite small, when viewed up close, some look rather allien-like. Also, this group contains a great deal of diversity in texture, shape, and color.

Note: Although the club mosses and spike mosses are more closely related to ferns than they are to mosses, I put them into this category, and I did this for two 'Very Lame' reasons: my first reason is for the fact that the word 'Moss' is a part of their common name...Such a botanical 'faux pas'! I hope that I'm not banished from my plant group! 😳 And my second reason is this; I didn't know where else to put them!🤔 - Sun Exposure

(5 choices): The choices are:

1)Full Sun, 2)Mostly Sunny, 3)Medium Sun,

4)Partial Sun, and 5)Full Shade.

Giving your plants the right amount of sun exposure can be quite a tricky endeavor...

If you are on a nature walk and you come across a particular plant that you like, mimic your planting site, to the best of your ability, to that of the plant as it sits in the wild. Take note of the amount of sunlight and moisture that it receives, as well as soil type, if possible. Also, just as important, take notice of the plants that it is growing under and near; there are a great deal of plants that depend on symbiosis for survival.

Symbiosis, by definition, is a close and long-term biological interaction between two different species; that of bees and flowers is probably the best example, but here, I am specifically refering to the interaction between fungi and plants. This particular partnership is called mycorrhizae, which is used by 80% - 90% of all land plants for their survival. In this association, the underground fungi colonize the root system of a host plant, providing increased water and nutrient absorption capabilities while the plant provides the fungus with carbohydrates formed from photosynthesis.

Below, is just a small sample of the untold number of our native flowering plants that use this intriguing survival technique:- Cypripedium acaule (pink lady's slipper)

- Aureolaria pedicularia (fern-leaved false foxglove)

- Monotropa uniflora (Indian pipe)

- Orobanche uniflora (one-flowered cancer-root)

- Melampyrum lineare (cow-wheat)

Back to Sun Exposure: On a sunny day, observe your chosen planting area in half hour increments; this will give you a better understanding of just how much sunlight is available. The time of year that you do your measuring is important; your chosen planting site will look much different in April, when the sun is lower in the sky and the trees have not leafed out yet, than it will in the summer when the sun is high and there is plenty of shade from surrounding trees and shrubs. Also, just as important, remember that morning sun is cooler than afternoon sun; by the time that the afternoon has rolled around, the sun has had a good part of the day to heat up the atmosphere.

Speaking of tricky: trying to determine my sun exposure choices was no picnic! In most of the literature that I read, partial sun and partial shade are interchangeable; how does that make any sense? Then there is 'medium/half shade'; what does that actually mean? And then you throw 'dappled shade' into the mix...all of this confusing info had left me quite perplexed!

In the end, I stuck with the conventional designations for full sun, partial sun, and full shade but added two more categories: mostly sunny and medium sun; I hope these make sense to others?

a) You will find that many plants can overlap sun exposure categories. Plants usually have a preference for their sunlight needs but can handle a little more, or a little less, light. A plant that moves into a little more sun may need additional water, while a plant moving into a little more shade may send out less flowers; some plants are perfectly happy in more than one category.Notes:

b) Plants from the nursery should have a sunlight requirement symbol/icon on them:

c) Dappled shade: I would expect that dappled shade could very well fit into any, or all of these categories, but, I believe it is meant to be a variation of the category, partial sun?

Full Sun - 6 or more hours of sun.

Partial Sun - 4 to 6 hours of sun.

Full Shade - 3 hours or less of sun.

- Full Sun: A planting location must receive 6 hours or more of sun each day to be

considered 'Full Sun'.

- Mostly Sunny: Even though these hours are based on that of the conventional 'partial

sun/partial shade' designation, I felt the need to clarify by adding this category. To me, partial shade and mostly sunny are the same thing, not partial sun and partial shade. The hours of sun that apply

here are 6 to 4, with the emphasis being on that towards the 'higher' end of 6 hours.

- Medium Sun: The term medium sun is one that still has me a bit baffled, but since

I had come across the term when doing my research, I felt it necessary to fit it into my website. From what I have gathered, I think that this term is meant to depict a planting site that has around two hours of direct sun,

preferably in the morning, or be shaded for half the day. A planting site that is situated under a roughly 50% tree canopy also fits into this category. When doing my research, I came across a website from Kansas City

that does a great job of breaking down the varying degrees of garden shade. I found the site,

K-STATE Research and Extention, to be the most helpful with this issue, but I

do have to admit that I am still a shade confused!🤭

- Partial Sun: To me, partial sun hints at being less sun than shade, so, the hours of

required sunlight for this category are between 4 and 6. This is similar to that of 'mostly sunny', but here, the emphasis is placed on that towards the lower end of 4 hours.

- Full Shade: This does not mean 'No Sun', instead, it means that the planting site should

receive less than 4 hours of sun each day, but, at least 2 hours of sun is recomended. As one would expect, there are not a lot of flowering plants that can handle Full Shade.

- Moisture Level

(5 choices): They are:

1)Dry,

2)Light, 3)Medium, 4)Moist, and 5)Wet.

As with 'sun exposure', how much water to give a plant and when to give it water can be a delicate balancing act; replicating the plant's natural habitat as closely as possible is always the best way to go.

In my research, the triad of terms xeric(of an environment or habitat) containing little moisture; very dry., mesic(of an environment or habitat) containing a moderate or well-balanced supply of moisture, and hydric(of an environment or habitat) containing plenty of moisture; very wet. were regularly used to describe the amount of water in a habitat. This may be over simplifying things, but I think that these are just a fancy way of saying dry, medium, and wet. I was not completely satisfied with these three conventional moisture categories so I added two others: light and moist. - Stick your finger into the soil, down to the second knuckle

- Stick a dry dowel into the soil; the dowel will turn a darker color, and soil will stick to it if there is moisture present

- or you can buy a moisture meter; they come in a wide range of prices

- Dry: Plants that prefer to be dry are generally drought

tolerant. They tend to grow in poor, sandy, or gravelly soil and love to bask in sunshine.

- Light: The plants that like 'light moisture' also like sandy

or gravelly soil and need to dry out completely between waterings; these plants suffer under drought conditions, but may rot under damp conditions.

- Medium: A wide range of plants fit into this category,

therefore, you will have plenty to chose from. As long as these plants are watered during dry spells and kept out of areas of prolonged standing water, they will do just fine.

- Moist: These plants cannot withstand prolonged dry

spells, but they can withstand seasonal flooding and wet feet. Most of our native plants that grow along river shores or in low lying areas fit into this category.

- Wet: This category is for those plants that have adapted to

growing in standing water or permanantly wet soil.

- Plant Height

(8 choices): They are:

1)Under 1', 2)1' - 2', 3) 2' - 3', 4)3' - 4',

5)4' - 6', 6)6' - 10', 7)10' - 30',

and 8)Over 30'.

Here, probably more than in any other category, there can be a great deal of over-lap. Many factors can alter a plant's height such as: habitat, soil type, moisture content, and sun exposure, just to name a few. For example, take a look at our beloved Eupatorium perfoliatum (common boneset), which can grow between 1' to 5' in height, depending on the afore mentioned factors.

So, please keep in mind that my listings are just a general guideline and that chosing your plants carefully may still result in one that may turn out to be a bit taller, or shorter, than expected; don't shoot the messenger; that's nature for you! 🤕 - Under 1': If you are looking for 'definite' shorties, ones

which prefer a sunny, sandy, fast draining location, then you can't go wrong with the quaint little Viola pedata (bird's-foot violet), or the fuzzy-looking, early season Antennaria neglecta (field pussytoes).

If you need something for a shady location, then you may enjoy one of our spring ephemerals, Anemone quinquefolia (wood anemone), or perhaps the lovely, purple Polygaloides paucifolia (fringed polygala).

- 1' to 2': In this group, I especially like Gentiana clausa

(closed gentian), mostly because I get a lot of enjoyment out of watching the bumblebees trying their darnedest to get into, and out of, the flowers.🤣

Another plant that fits into this category is a wonderful little shrub whose botanical name is bigger than the plant itself; it is Vaccinium angustifolium (lowbush blueberry).

- 2' to 3': For this group, I like a couple of

sun-lovers: my first selection is a perennial from the mint family, Pycnanthemum muticum (mountain mint), and my other selection is a shrub and a pollinator-magnet; it's Ceanothus americanus (New Jersey tea).

- 3' to 4': Apocynum cannabinum (Indian hemp), with its

beautiful deep-red stems, fits into this category, as does the aptly-named, summer-blooming shrub, Spiraea tomentosa (steeplebush), with its lovely pink spires.

- 4' to 6': Senna hebecarpa (wild senna), with its yellow,

pea-shaped flowers and fern-like foliage, and Veronicastrum virginicum (Culver's-root) with its white, multi-branched flower-spikes, fit into this group. I have not had the pleasure of seeing either of these plants

growing in the wild. I have only seen them in a native planting bed.

- 6' to 10': When walking along open, wet areas, you have a

good chance of seeing this shrub, Cephalanthus occidentalis (buttonbush), with its white, ball-shaped flowers.

One of our taller perennials, Rudbeckia laciniata (green-headed coneflower), also fits into this category; it can reach heights of around 9'.

- 10' to 30': We are now getting into the 'height category'

of the woody plants; one of my favorites is the lovely, early-flowering shrub, or small tree, Amelanchier arborea (downy servicberry).

There are members of this group which reside in a genus that I once viewed as bothersome weeds; they are the sumacs. Nowadays, spotting their bright-red, life-sustaining, berry-like fruit on a frigid winter's day is indeed a very welcome sight; the winter birds truly enjoy their seeds.

Believe it or not, there is also an annual that fits into this category; it is the climbing vine, Echinocystis lobata (wild cucumber). This vine can reach lengths of up to 15' during its single growing season...Talk about a growth spurt!

- Over 30': Now we have entered tree territory! I

am rather limited in tree photos at this time, (2023), perhaps because they are well beyond my eye level? I am dead set on rectifying this matter because trees deserve to be admired just as much as any other plant;

after all, where would our enderstory plants and spring ephemerals be without the the majestic tree!

I welcome the prospect of finding Betula papyrifera (white birch), with its white, peeling bark that just pops when viewed against a deep-blue sky, which I usually don't have!😞.

Another tree that I enjoy seeing is a new introduction to me, Larix laricina (tamarack); there is something that is rather uniquely appealing about a deciduous conifer, and to top it all off, this conifer's needles turn a beautiful shade of yellow-orange before dropping in late autumn.

- Bloom Season

(8 choices): They are:

1)Late Winter,

2)Early Spring, 3)Mid Spring, 4)Late Spring, 5)Early Summer,

6)Mid Summer, 7)Late Summer, and 8)Fall.

Important! When viewing a plant's bloom season on this site, as well as most other websites for that matter, there is one thing that you should keep in mind: first, and foremost, the bloom season that is depicted represents the time at which a plant may flower over the entirety of its native range...This should not be confused with its time in flower. If you research a plant, which I strongly suggest that you do, you will often come across a phrase such as this, "The blooming period occurs during late spring to early summer and lasts about 2-3 weeks." Here, the reader is being informed that this particular plant will flower for about 15 to 20 days, anywhere from early/mid May to late June/Early July, depending on where you live. I felt that I had an obligation to my readers to try and clarify this often over-looked, and often misunderstood, piece of information. The fact is, the majority of our flowering plants bloom for roughly two to three weeks, not for several months. There are some plants, such as Apocynum cannabinum (Indian hemp), Euthamia graminifolia (flat-top goldentop, grass-leaved goldenrod), and some others that flower for a month or more, but for the most part, they are the exception rather than the rule.

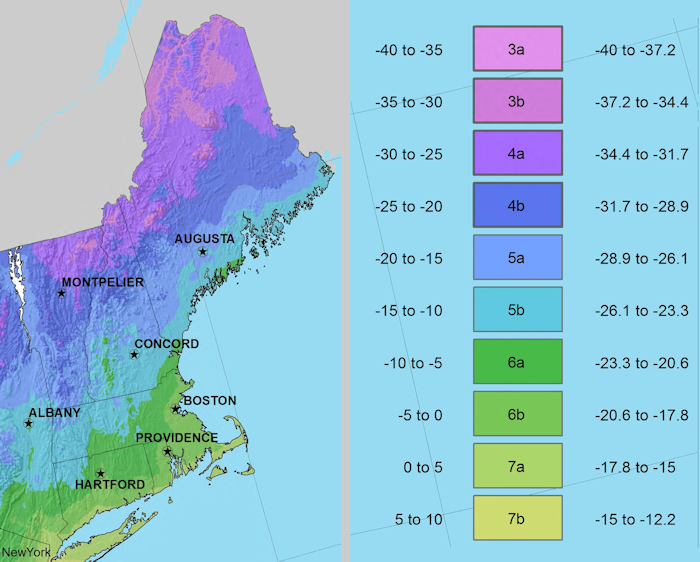

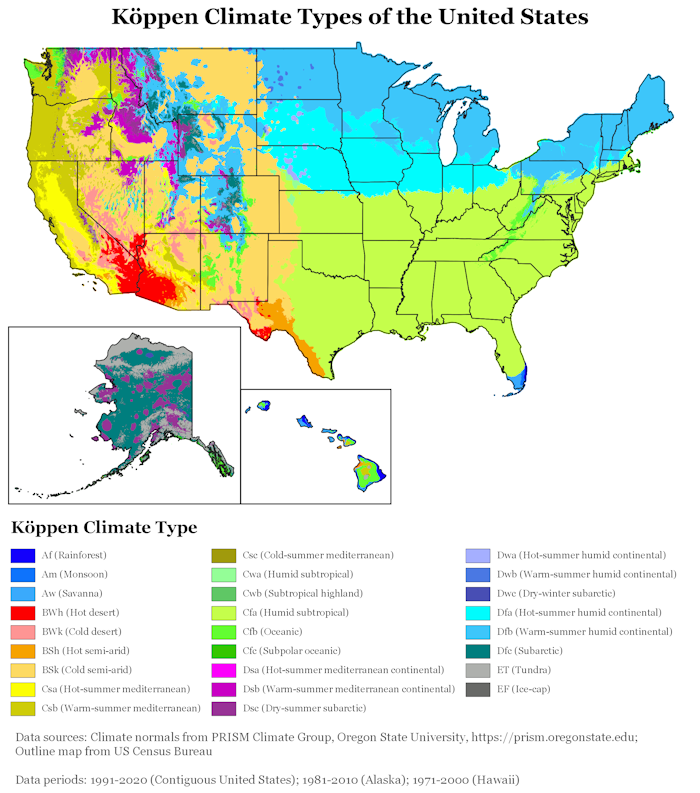

Bloom season is a hard category to pin down because there are so many factors that can alter the time at which a plant will flower; the most noteworthy of these being your Hardiness Zone ...not to be confused with 'Climate Zone

...not to be confused with 'Climate Zone

'. The weather, be it hot, cold, wet, or dry, especially for extended periods, will also affect flowering time, as will the creation of micro climates within your comunity, or

even your own yard. Also, a stressed or damaged plant, whether it's from insects, man, weather, or something else, can trigger a plant into activating its flowering process.

'. The weather, be it hot, cold, wet, or dry, especially for extended periods, will also affect flowering time, as will the creation of micro climates within your comunity, or

even your own yard. Also, a stressed or damaged plant, whether it's from insects, man, weather, or something else, can trigger a plant into activating its flowering process.

Taking all of this into account, I did my best with determining a plants 'Bloom Season'. Since New England is represented by several hardiness zones, your plant's bloom season will depend, for the most part, on your location. The plant photos displayed within this site were taken in and around my area of MA , which is on the border of zones 5 and 6. It has

reached -14°F here at my home a couple of times over the past decade, so I urge you to err on the side of caution when chosing plants that are on the borderline of your cold hardiness zone.

, which is on the border of zones 5 and 6. It has

reached -14°F here at my home a couple of times over the past decade, so I urge you to err on the side of caution when chosing plants that are on the borderline of your cold hardiness zone.

- Late Winter: At this time of year, plants in flower are somewhat hard to come by, but

these two plants can handle the cold weather quite well:

One is the shrub, or small tree, Alnus incana subsp. rugosa (speckled alder).

The other selection is a rather well-known, wetland, perennial which, by means of a chemical process, is capable of producing heat in excess of 60°F. This process allows it to melt through the surounding snow and ice and prevents the flower from freezing...You guessed it! It's Symplocarpus foetidus (eastern skunk cabbage).

- Early Spring: A couple of tough plants that can handle the unpredictable temperatures of

early spring are Epigaea repens (trailing arbutus), with its sweet smelling, ground-hugging, white, or pink flowers, AND everyone's favorite, Salix discolor (pussy willow); who can resist those fuzzy, silver catkins.

- Mid Spring: This is around the time of year when the daytime temperatures tend to stay

above freezing, for the most part. It's a particularly fun time for me as I thoroughly enjoy trying to photograph the early pollinators that visit our little Houstonia caerulea (bluet, azure bluet, Quaker Ladies).

It is also the time of year when one of my favorite shrubs is in flower; it's Lindera benzoin (spicebush), which happens to be a host to the spicebush swallowtail butterfly.

- Late Spring: With the temperatures stabilizing in late spring, a wealth of native flowers

appear. A couple of my favorites for this time of year are the moisture-loving Iris versicolor (northern blue flag), and the adaptable, evergreen, shrub, Kalmia angustifolia (sheep laurel).

- Early Summer: The consistantly warm weather of early summer means that the flowering

season is booming. Here are two great pollinator plants from this group: first, the bright-yellow Baptisia tinctoria (yellow wild indigo), and the abundant, daisy flowered, Erigeron annuus (annual fleabane).

- Mid Summer: By mid summer, the vast majority of our early season flowers are done blooming,

and our spring ephemerals have pretty much withered away; this is the time that our warm season natives take over. A couple of plants from this group are Verbena hastata (blue vervain), and the prolific pollinator

magnet; it's Monarda fistulosa (wild bergamot, wild bee balm).

- Late Summer: When late summer arrives, you never know what you are going to get for

temperatures. The heat and humidity in the early part of late summer can become unbearable, while by its tail end, the cooler temperatures will spark the onset of autumn colors. Regardless, there's an abundance of plants

that are in flower at this time of year. Here are a couple of late summer bloomers: first is a lover of open, sandy areas; it is Liatris novae-angliae (New England blazing-star), and next, a plant that prefers a bit of

moisture; this is Chelone glabra (white turtlehead).

- Fall: This is the time of year when the amount of daylight begins its decline, and

although there are other plants still in flower, the goldenrods and asters are king. I have a hard time identifying members of these groups, but I have managed to ID a few of them. First up is the appropriately named

Solidago rugosa ( wrinkle-leaved goldenrod), and next up is Symphyotrichum pilosum (hairy white oldfield aster, frost aster): both plants get a lot of insect lovin'.

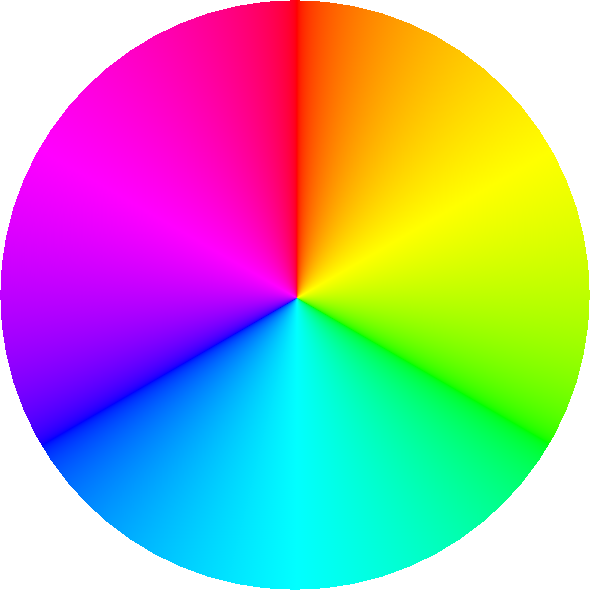

- Flower Color

(9 choices): They are:

1)White, 2)Yellow, 3)Orange, 4)Purple,

5)Blue, 6)Pink, 7)Red, 8)Green,

and 9)Brown.

I thought that creating this category was going to be an easy task; after all, how hard can it be to choose colors? Well, I thought wrong; as my wife would say, "Don't ever give a man too many choices!"🤯

The flowers entered into the White category were fairly easy to dertermine, as were those for the colors of Brown and Green, but after that... The party was over!Here was my dilemma: Where do you draw the line between the colors of yellow and orange? Or orange and red? And then there is red and pink. And pink and purple. And we cannot forget about purple and blue. All of this was giving me a headache and messing with my eyes, and then I thought to myself, "What about the multi-colored flowers!"😵

In any event, once I regained some semblence of my former sanity, I broke my list down to 9 color choices, and wouldn't you know it; according to my computer's paint program, I'm only a mere 16,777,207 colors shy of the possible color choices .🥴

.🥴

In short, when searching for your flowers "by color", on this site, keep a couple of things in mind:

- If I came across a plant whose flowers were somewhere in between two of my color choices, or they were multi-colored flowers, I put the plant into all of the possible color choices for that particular plant.

- A flower may have the appearance of a different color when it resides in shade as opposed to being in bright sunlight; some also change colors as they age; in these cases, I also put the plant into all applicable categories.

Good Luck!

- White: Your choices for a white-flowered plant are pretty

much endless; so, for this selection, I picked a couple of plants that are not your run-of-the-mill selections. First is a cute, little, wetland perennial, Eriocaulon aquaticum (seven-angled pipewort), which reminds me

of a childhood candy called 'Snow Caps'. The second is a much taller, late-season perennial from the Aster (Asteraceae) family; it's Nabalus alba (white rattlesnake-root).

- Yellow: As with the whites, your choices for a

yellow-flowered plant are limitless. Here, I chose two plants which are quite charming in their own way. The first is one of our spring ephemerals, Erythronium americanum (yellow trout lily), with its mottled leaves and

little lily-like flower, and the second is the under-used, long-flowering Helenium flexuosum (purple-headed sneezeweed), with its maze-patterned button center and recurved-ray petals.

- Orange: Orange, or is it yellow-orange,

or orange-red?.🤣 Here, are a couple of flowers that I know are orange. How do I know that they are orange? It's obvious; it says so in their common name!😂

Now that I got that out of my system, here is my first selection; it's probably our most well known orange perennial, Asclepias tuberosa (butterfly weed, orange milkweed). Although this plant is sometimes refered to as orange milkweed, this species does not have milky sap.

My next selection is probably our most well known orange annual. Here is Impatiens capensis (orange jewelweed); it is not just the insects that love these flowers!.

- Purple: Purple, Plum, Orchid, Violet, Magenta, Whatever!

If any of the flowers in this group look either pinkish or blueish, they may just be. OR, maybe it was the lighting, the flower's age, or who knows what else? In any event, I chose a couple of flowers that always appear

to be purple to me. The first is Pontederia cordata (pickerelweed), a wonderful plant for a pond or rain garden, and the other is Triodanis perfoliata (clasping Venus' looking-glass), an annual that likes dry open

areas with sharp drainage.

- Blue: Blue is a bit of a misleading term when it comes to

describing flowers; blue flowers, for the most part, are usually just a shade of purple. Blue is the rarest color for flowers, and for that matter, the rarest color in nature. Creating the color blue, in nature, is a

complex matter that has to do with pigment, anthrocyaninsAnthocyanins, also called anthocyans, are a class of water-soluble phytochemical compounds widely present in plants, fruits,

vegetables, and leaves., soil ph, and reflective light. For those of you who may be interested as to why the color blue is so rare, this webinar,

Elusive Blue: the Rarest of Flower Colors, from Cornell University, is great; it's an hour long, but great none

the less!

A good many of our beautiful native plants that are refered to as blue, as I mentioned earlier, are usually just some shade of purple: blue flag, blue vervain, forked bluecurls, and blue toadflax are just a few that come to mind. Having said that, here are my two picks for the group, Blue. First, is Gentianopsis crinita (fringed gentian), a real beauty; when viewed in the right light, it really does look blue.

Next up is Sisyrinchium atlanticum (eastern blue-eyed grass); the flowers of this perennial are more of a pale shade of blue, at least through my eyes, but a 'blue' none the less.

- Pink: For this color, I chose a couple of our native orchids.

First in line, is a plant that has been a favorite for many a generation; it is the woodland wildflower, Cypripedium acaule (pink lady's slipper). I never get tired of coming across this jewel in the wild.

My other selection for this color is Pogonia ophioglossoides (rose pogonia), a plant of acidic wetlands, were I observe it floating on mats of sphagnum. When observed on an overcast day, the color leans towards the orchid/plum/purple section of the color spectrum, but in bright sunlight, it looks to be a translucent pink.

- Red: My first selection for the color 'red' is a plant that

is familiar to most. It is fond of woodland and rocky slopes, and it has dangling red and yellow flowers; it's the charming Aquilegia canadensis (eastern red columbine).

My second selection for this color group is the 2 - 3 foot, berry producing shrub, Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry); this shrub also has vibrant red fall foliage.

- Green: Yes, I had to add the color 'green' to this group

because there are native plants out there whose flowers do cantain some degree of green in them. One such plant is the aptly named, native orchid, Platanthera lacera (ragged fringed orchid), whose ragged-looking

flowers appear to be some color combination of creamy-white and yellow-green.

Another plant for this group has a flower that really is a shade of green, but I don't know what shade that may be. Although the flowers are not show-stoppers, I am especially fond of them because they truly are different, and the insects are quite attracted to them. Also, the foiliage, like the flower petals, is unique with its many vertical ribs. The plant is Veratrum viride (false hellebore). Please be aware that all parts of this plant are toxic.

- Brown: Yup!

Brown, and I created this category for the same reason that I created the 'Green' catergory; we do have brown flowers out there...sort of !

Both of my choices for this color are kind of odd-balls. One is a woodland perennial, and whenever I see it in bloom I say to myself, "What the heck...How is that considered a flower!" It more closely resembles a grappling hook than a flower...I am referring to the curiosity of nature, Medeola virginiana (Indian cucumber-root).

My other choice for the 'brown' flower group doesn't even look like a plant, never mind a flower. It is a parasitic nemesis of the black spruce (Picea mariana), and other conifers, but I have only photographed it on the black spruce.

This tiny little thing slowly saps the life out of the tree: It causes its host to produce fewer, smaller, yellower needles and as an infection proceeds, it decreases the tree's growth and reproduction, increases susceptibility to other damaging agents, and eventually results in crown dieback and death: (Geils and Hawksworth 2002, Baker et al. 2006).

This little buggar is Arceuthobium pusillum (eastern dwarf mistletoe).

Note: I can't believe that I have to say this, But, do not eat any mushroom that you cannot identify! 🙄

Notes:

a) Also, as with 'sun exposure', some plants can be happy in more than one moisture category. When taking a plant away from its prefered moisture needs, drainage, or the lack of, and the amount of sun exposure, will more than

likely be the key to its survival.

b) Plants from the nursery should have a moisture requirement symbol/icon on them:

💧 = Dry

💧 💧 = Medium

💧 💧 💧 = Wet

c) Determining if your soil is moist is a pretty straight forward endeavor. You can either: